EV Charging Infrastructure: Strategic Planning for 2025-2030

Data current as of January 2025 | UK charging infrastructure data from GOV.UK

If you're responsible for EV charging infrastructure decisions, whether as a local authority, property developer, fleet operator, or business owner, you're making choices now that will define your position for the rest of the decade.

The numbers tell part of the story and set clear targets, such as 300,000 public charging points by 2030, helping stakeholders stay focused on planning goals.

But the real questions aren't about hitting government targets. They're about making decisions that still make sense in 2028, when vehicle capabilities have changed, usage patterns have shifted, and the competitive landscape looks completely different from today.

This guide addresses strategic planning for EV charging infrastructure through to 2030. Not the usual surface level overview that repeats government press releases, but the practical considerations that determine whether your infrastructure investment delivers value or becomes an expensive mistake.

Where We Are: The Current State of UK Charging Infrastructure

Understanding the starting point helps with realistic planning. Note that charging infrastructure is growing rapidly (37% during 2024), so statistics become outdated quickly.

The numbers

The UK had approximately 73,000 public charging devices as of January 2025, with the network growing by 37% during 2024 alone. By November 2025, this figure had risen to over 87,000 devices. This includes around 14,500 rapid chargers (those at 50kW and above, representing 20% of the total) and roughly 59,000 slower destination chargers at locations where vehicles park for extended periods.

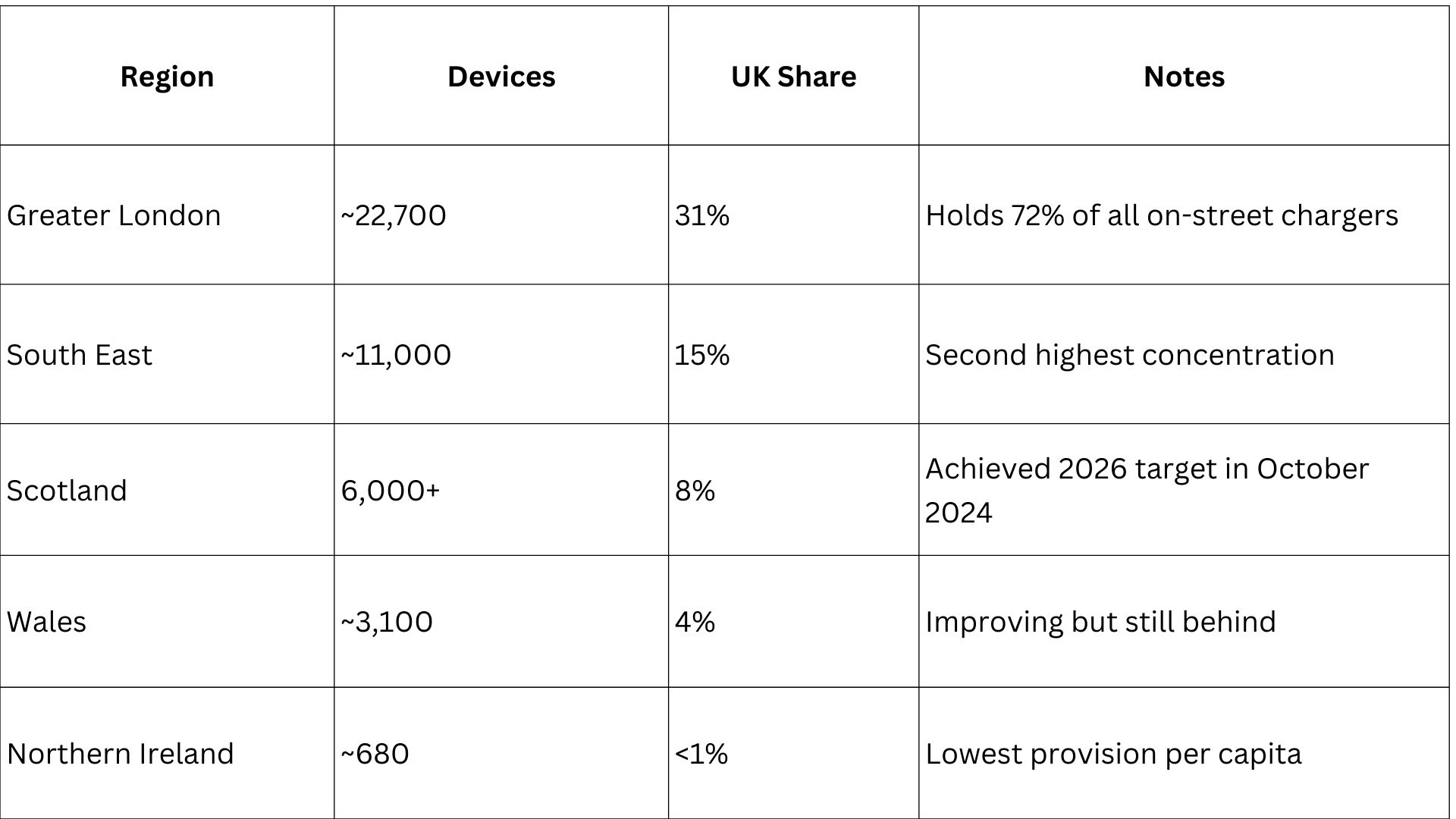

UK Charging Infrastructure by Region

Scotland's achievement deserves particular attention. Transport Scotland confirmed in October 2024 that Scotland had reached 6,007 public charge points, surpassing its 6,000 target two years ahead of the 2026 deadline. The network grew by 49% between June 2023 and October 2024, supported by a £30 million EV Infrastructure Fund for local authorities. Scotland has now set a new target of 24,000 additional charge points by 2030.

Geographic inequality

The distribution isn't just London centric. It's heavily skewed towards affluent areas with newer housing stock and commercial centres. Rural areas, older housing estates, and regions with lower car ownership have far fewer charging options.

This creates a genuine barrier to EV adoption in areas that could benefit most from lower running costs. Someone in central Edinburgh can easily find a charger; someone in an ex-mining town in County Durham faces an entirely different situation.

The on-street parking challenge

According to the RAC Foundation's 'Still Standing Still' report, approximately 35% of UK households lack off-street parking (or alternatively, 65% have or could accommodate off-street parking). Field Dynamics research puts the figure at 6,642,000 households (24.6%) without space to park and charge off-street. The variation reflects different methodologies and definitions.

The situation is considerably worse in urban areas:

- Greater London: 56% of households lack off-street parking (London Assembly Research Unit, November 2024)

- Westminster: Only 7% have private off-road parking

- Tower Hamlets: Only 7% have private off-road parking

- Islington: Just 14% have private off-road parking

These households can't install home chargers and depend entirely on public infrastructure. Current provision doesn't come close to meeting this need. On-street charging remains patchy, expensive, and often inconvenient compared to home charging.

Emerging solution: Cross-pavement charging. In July 2025, London Councils published new guidance on cross-pavement EV charging solutions, which allow residents without driveways to charge at home using either surface 'gullies' or buried cable systems. The government has allocated £25 million in funding for local authorities to install these solutions. Installation costs typically range from £1,000 to £1,500 and take 1.5 to 3 hours to complete.

Rapid vs destination charging

The mix of charger types matters.

- Rapid chargers (50kW+): Suit motorway services and quick top-ups

- Destination chargers (7-22kW): Work for locations where people park for hours, such as supermarkets, leisure centres, and workplaces

The UK has prioritised rapid charging, particularly along motorway corridors. That makes sense for long-distance travel. But destination charging at everyday locations remains underdeveloped relative to need.

2030 Targets: What Government Actually Expects

Government targets provide context.

The 300,000 target

The government expects 300,000 public charging points by 2030, a target set out in the March 2022 Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Strategy. Analysis from ChargeUK and the National Infrastructure Commission suggests the UK is on track if current growth rates continue.

This breaks down roughly into: thousands of rapid chargers along motorway and trunk road networks; tens of thousands of rapid chargers at fuel stations and hub locations; and the remainder as destination chargers at shops, workplaces, and residential areas.

These aren't mandates. They're projections based on assumed EV adoption rates and charging behaviour. Whether they're achievable depends entirely on commercial investment and local authority action.

Important funding change: The original £950 million Rapid Charging Fund for motorway infrastructure was scrapped in June 2025. Originally announced by Rishi Sunak in March 2020 with plans for 6,000+ rapid and ultra-rapid chargers at motorway services by 2035, the pilot was delayed multiple times before being cancelled entirely. The Department for Transport cited lack of interest from motorway service operators and noted that private investment had already quadrupled the rapid/ultra-rapid charging network between 2021 and 2024. The £400 million has been redirected towards on-street residential charging provision instead.

The 2030 petrol and diesel ban

New petrol and diesel car sales end in 2030 (with hybrids allowed until 2035). This target was formally reinstated on 6 January 2025 after a brief delay under the previous government. This drives everything else. If new vehicles are predominantly electric from 2030 onwards, the charging infrastructure needs to be primarily in place by then, not just planned, but actually installed and operational.

Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate

The ZEV Mandate became law on 3 January 2024, placing legally binding quotas on manufacturers for EV sales:

- 80% of new cars must be zero-emission by 2030

- 70% of new vans must be zero-emission by 2030

- 100% of both must be zero-emission by 2035

The 2024 targets were 22% for cars and 10% for vans, with the actual EV market share reaching 19.6%. The 2025 targets rise to 28% for cars and 16% for vans.

April 2025 updates introduced several flexibilities: non-compliance penalties reduced from £15,000 to £12,000 per car and from £18,000 to £15,000 per van; borrowing provisions were extended to 2029; and CO2 credit transfer provisions were extended. Small manufacturers (under 2,500 cars per year) remain exempt until 2035. No manufacturers paid fines in 2024 due to the available flexibilities.

Local authority obligations

Councils have duties under the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 to provide charging infrastructure in their areas. The specifics remain vague, with 'appropriate provision' offering no precise guidance. But the direction is clear: this is a local authority responsibility, whether they have the budget for it or not.

Understanding Available Funding Options

Planning requires understanding available funding, its limitations, and how it's likely to evolve.

Government Grant Programmes

Local Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (LEVI) Fund

The LEVI fund provides capital grants to local authorities for charging infrastructure in residential areas. The total allocation is £381 million, comprising £343 million for chargepoint installation and £37.8 million for local authority capability building.

What it covers:

- Capital costs for charger installation, particularly on-street and in car parks serving residents without driveways

- Strategy development and planning work

What it doesn't cover:

- Ongoing operational costs

- Maintenance

- Electricity costs

- Commercial deployment beyond residential needs

The reality: LEVI funding helps but doesn't come close to covering full infrastructure needs. The first LEVI-funded installations began in September 2025, with over 100,000 local chargepoints expected from the programme. However, progress has been slower than hoped: by October 2024, only 10 of 78 projects had been approved against a March 2025 deadline. Councils need to supplement this funding with commercial partnerships and revenue from charging operations.

Workplace Charging Scheme

Businesses and charities can claim grants covering 75% of total costs (purchase and installation including VAT) for workplace charging infrastructure:

- £350 per socket, up to 40 sockets across all sites

- State-funded educational establishments: £2,500 per socket (a significant increase to support schools and colleges)

Over 1,400 sockets have been installed at UK schools and colleges through this scheme. Applicants must use OZEV-approved installers and have designated off-street parking.

EV Infrastructure Grant for Staff and Fleets

This separate scheme for SMEs (businesses with 249 or fewer employees) provides:

- £350 per charging socket

- £500 per parking space for supporting infrastructure

- Maximum of £15,000 per property

- Up to five grants for different properties

Both schemes close on 31 March 2026. Planning around specific grant programmes requires accepting that terms change frequently. Don't build a strategy around funding that might not exist in 18 months.

Commercial Funding Models

Most charging infrastructure will ultimately be commercially funded. Understanding viable business models matters more than chasing grants.

Direct ownership: You fund and own the infrastructure, keeping all revenue. This works if you have capital available and expect utilisation sufficient to generate acceptable returns.

Typical costs:

- 50kW rapid chargers: £15,000-35,000

- 100kW+ ultra-rapid installations: £35,000-80,000

- Destination chargers: £5,000-15,000

- Single 7kW units: potentially as low as £1,000-1,500

Charge point operator partnerships: A CPO installs, owns, and operates the infrastructure on your site. You provide the location and potentially the power supply, but don't fund the hardware or costs associated with maintenance and replacement. Revenue share varies based on contributions. This model reduces your capital requirement to near zero whilst still providing charging facilities. The trade-off is lower revenue per session since the CPO takes a share.

Lease arrangements: You own the chargers but lease management and operations to a specialist provider. This keeps you in control of the asset whilst outsourcing technical complexity.

Advertising-funded: Some models use advertising on charging stations to offset installation and operating costs. This works in high-footfall locations but isn't realistic everywhere.

.jpg)

Strategic Planning for Local Authorities

Councils face the challenge of providing infrastructure with limited funding, uncertain demand projections, and political pressure to move quickly.

Starting with strategy

The temptation is to install chargers wherever grant funding permits. This can create patchy provision that doesn't serve actual need.

Better approach: Start with a proper needs assessment by asking these questions:

- Where are your residents without off-street parking? Map your housing stock. Identify concentrations of terraced housing, flats, and other properties without driveways.

- Where do people actually park? On-street charging works where people park overnight. If your town centre empties at night, putting chargers there doesn't help residents.

- What's your fleet transition plan? Your own council fleet provides a base load of demand. Electrifying council vehicles provides a clear use case for workplace charging infrastructure.

- What's your spatial development plan? New housing developments require charging infrastructure. What's being built, where, and what's the developer's contribution?

Prioritisation frameworks

You can't install chargers everywhere at once. Prioritisation matters.

- Highest impact first: Areas with the most residents lacking off-street parking, the highest car ownership, and current barriers to EV adoption

- Geographic equity: Political reality means you can't just focus on dense urban areas. Rural areas need provision too, even if the business case is weaker

- Strategic locations: Town centres, transport hubs, and major destinations serve multiple purposes

Procurement approaches

How you procure infrastructure affects what you get and how much it costs:

- Framework agreements: Using established frameworks (such as CCS for local authorities) speeds up procurement and provides pre-negotiated terms. The trade-off is less flexibility

- Direct commercial partnerships: Working directly with charge point operators provides more tailored solutions but requires proper due diligence. Make sure partners use open standards like OCPP to avoid vendor lock-in

- Community energy schemes: Some councils have worked with community energy groups to deploy charging infrastructure. This engages local stakeholders and can access different funding streams

Revenue and sustainability

Charging infrastructure has ongoing costs: electricity, maintenance, network management, and customer support. Grant funding might cover installation, but who pays for operations?

- Operating cost recovery: Charging fees need to cover electricity and operational costs at minimum

- Resident vs visitor pricing: You might charge residents lower rates than visitors, particularly for on-street charging

- Long-term financial sustainability: Create realistic 10-year financial models. Factor in declining utilisation of slow chargers as vehicle ranges improve

Strategic Planning for Businesses

Commercial organisations face different drivers and constraints from local authorities.

Why install charging infrastructure?

Get clear on your objectives. Different goals require different approaches:

- Customer attraction: Retail locations increasingly compete on amenities. EV drivers actively seek charging locations

- Employee benefit: Workplace charging attracts and retains staff, particularly those considering EV purchase

- Fleet transition: If you operate vehicle fleets, workplace charging infrastructure is essential

- Planning requirements: New developments increasingly require EV charging provision

- Corporate sustainability: Charging infrastructure supports ESG goals and demonstrates commitment to decarbonisation

Workplace charging: Getting it right

Workplace installations differ from public charging in essential ways:

- User base: You know exactly who will use your chargers, your employees

- 7kW chargers usually suffice: An employee parking for 8 hours at a 7kW charger adds roughly 50-60 miles of range

- Access control: You may want to restrict charging to employees, possibly with preferential pricing

- Future capacity: Install electrical infrastructure that can support more chargers than you install initially

Every site’s needs will be different, but starting with 10-15% of parking spaces with charging and planning electrical capacity for 30-40%. This gives you headroom without massive upfront costs.

Retail and leisure: Customer charging

Customer-facing charging follows a different logic.

- Dwell time matters: If customers spend 10 minutes, rapid charging might work. If they spend two hours, destination charging is fine and much cheaper

- Volume vs margin: Rapid charging generates revenue through volume. Destination charging generates value by attracting customers who spend money while their cars charge

- Location visibility: Charging infrastructure should be evident from the road if you want to attract passing EV drivers

Hospitality: The overnight advantage

Hotels and similar accommodations have particular opportunities.

- Overnight charging: Guests park for 8-12 hours. Even basic 7kW charging delivers a full charge overnight

- Competitive advantage: Hotel selection for many EV drivers now includes charging availability

- Premium service opportunity: Charging can be a revenue stream or an included amenity (like WiFi)

Technology Choices That Matter

The infrastructure you install now needs to work well through 2030 and beyond. Some technology decisions affect long-term viability more than others.

Open standards are non-negotiable

Install OCPP-compliant infrastructure. This protects your investment by allowing you to switch management platforms if needed.

Proprietary systems look attractive initially, perhaps with lower upfront cost or integration with other services you use. But they create permanent dependency on a single vendor. Over a 10+ year lifespan, that dependency will cost you far more than any initial savings.

Right-sizing charger power

Bigger isn't always better:

.jpg)

Installing unnecessarily powerful chargers wastes money on installation if you’re funding the project, increases ongoing electricity costs, and risks being too expensive and mismatched to customer needs. Match power to actual use cases.

Future-proofing without over-specifying

You can't predict exactly what 2030 will look like. But you can make sensible choices:

- Install capacity for future expansion: Electrical infrastructure should support more chargers than you initially install

- Choose scalable management platforms: Cloud-based systems scale easily. On-premise systems often don't

- Consider vehicle-to-grid readiness: Using open standards like OCPP helps ensure compatibility with future capabilities

Grid Connection: The Hidden Challenge

Getting power to charging infrastructure proves more difficult than many people expect.

Understanding your electrical capacity

Adding EV chargers obviously increases electrical demand. The question is whether your existing electrical supply can handle it.

Simple calculation:

- A single 7kW charger draws about 32A

- A 50kW rapid charger draws around 72A per phase on a three-phase supply

- Multiple chargers operating simultaneously need additional capacity

When grid upgrades are needed

If your existing supply can't support the planned charging infrastructure, you need a grid connection upgrade:

- Simple upgrades: £10,000-20,000

- Complex upgrades requiring new substations: Can exceed £100,000

- Rural locations often face higher costs than urban areas

Meaningful change since April 2023: Under Access SCR rules, demand customers no longer pay for DNO network reinforcement, only extension assets connecting to your site. This has reduced costs significantly for many installations.

Timelines: Plan on 6-18 months from application to energisation for complex upgrades. ChargeUK reports substantial bottlenecks at some DNOs, so factor this into your project timeline.

Smart charging and load management

Smart charging can reduce or eliminate the need for grid upgrades.

Rather than providing full power to every charger simultaneously, load management distributes available power intelligently. If you have 100kW available and ten 7kW chargers, the system ensures the total draw stays below 100kW by dynamically adjusting the power of individual chargers.

The trade-off: Users might experience slower charging during peak periods. For workplace charging where vehicles park all day, this doesn't matter. For rapid charging, where people want speed, it's more problematic.

Operational Considerations

Installing infrastructure is just the beginning. Ongoing operations determine whether your investment delivers value.

Maintenance and reliability

Charging infrastructure requires maintenance. Connectors wear out. Software needs updates. Things break.

- AC destination chargers: £90-300 annually for basic maintenance

- DC rapid chargers: £500-1,000 per year for comprehensive service contracts

Have a straightforward process for handling faults and a contractor who can respond within 24-48 hours. Target 95%+ uptime as a minimum.

Customer experience

How users interact with your charging infrastructure affects whether they use it again.

- Payment options: Support multiple methods: app-based, contactless card, roaming services

- Pricing transparency: Display pricing clearly. Per-kWh pricing is more transparent than per-minute

- Physical design: Chargers should be easily accessible. Lighting matters: charging happens at night too

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Learning from others' expensive errors beats making them yourself:

- Installing chargers before understanding demand: Putting chargers where funding permits rather than where people need them wastes money

- Choosing chargers based solely on price: The cheapest hardware often proves most expensive over its lifetime

- Ignoring electrical capacity until it's too late: Grid connection issues can delay or stop projects or lead to massive unexpected costs

- Single-vendor lock-in: Proprietary systems create permanent dependency. Use open standards

- Forgetting ongoing operational costs: Electricity, maintenance, management, and support expenses often get neglected

- Over-specifying power requirements: Installing 150kW ultra-rapids at a workplace where 7kW chargers would suffice wastes enormous sums

Getting Started: Practical Next Steps

For local authorities

- Conduct proper needs assessment: Map housing stock, identify areas without off-street parking, understand current and projected EV adoption

- Develop spatial strategy: Prioritise locations based on need and impact. Create a phased deployment plan

- Explore funding options: Apply for LEVI funding and other relevant grants

- Procure or partner: Use frameworks for speed or run a competitive process. Ensure partners use open standards

- Assess electrical capacity: Work with your DNO to understand capacity at priority sites or choose a partner who handles the DNO relationship

- Implement with evaluation: Monitor utilisation, gather feedback, adjust plans

For businesses

- Define objectives clearly: Customer attraction, employee benefit, fleet transition, or planning requirement?

- Assess electrical capacity: What's your current supply? Do you need upgrades?

- Evaluate funding options: Check eligibility for workplace charging grants

- Match technology to use case: Workplace? 7kW. Retail with short dwell time? Rapids. Hotel? 7kW overnight

- Choose delivery model: Own and operate? Partner with a CPO? Lease management?

- Implement and learn: Start small. Scale based on demonstrated demand

The 2025-2030 Outlook

The next five years will see more change in EV charging infrastructure than the previous decade.

What's likely

- Vehicle ranges will increase. The average EV in 2025 achieves around 300 miles on official WLTP tests, though real-world driving typically delivers 220-240 miles

- Rapid charging will continue spreading. Journey charging along motorways and A-roads will be well-served by 2027-2028

- Home charging will remain the most convenient and cheapest option. Around 65% of UK households have or could accommodate off-street parking

- Workplace charging becomes more important as a bridge for those without home charging

- On-street residential charging remains a complex problem. This is where local authority action matters most

What's uncertain

- Will battery swapping emerge as an alternative? Probably not for cars, but possibly for commercial vehicles

- How quickly will vehicle-to-grid become commercially important?

- What happens to petrol stations? Some transition to charging hubs. Others close

- How does automated driving affect charging infrastructure?

Why This Planning Matters

EV charging infrastructure decisions you make now affect your position for the rest of the decade.

Install the wrong technology or in the wrong locations, and you've wasted capital on stranded assets. Choose vendors with proprietary systems, and you're locked in for 10+ years with no negotiating power.

But get it right, installing appropriately sized infrastructure in locations serving real need, using open standards that protect your investment, and you're well positioned regardless of how the details evolve.

The planning matters more than specific predictions. Build in flexibility. Avoid lock-in. Start with clear objectives. Make decisions that remain defensible even if circumstances change.

That's the strategic approach that works through to 2030 and beyond.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(4).jpg)

%20(3).jpg)